After my last post discussing how to develop a research question, Sergey Kryazhimskiy asked me to write about how to find the rare good research idea among the many mediocre ones.

@ClausWilke After 2 successful projects the problem shifts to choosing a rare good research idea among many mediocre ones. Next post? 2/2

— Sergey Kryazhimskiy (@skryazhi) June 16, 2014

The truth is that I don’t really know how to do this. If you do, please tell me. I’m sure I could strengthen my research program by picking better problems. Nevertheless, despite my ignorance, I’ve had a reasonably successful career to date. And it was probably not entirely due to sheer luck. So this should give you hope. Even if you don’t know how to pick good problems, you may succeed in science nonetheless. Just work on the problems that seem important to you and hope for the best.

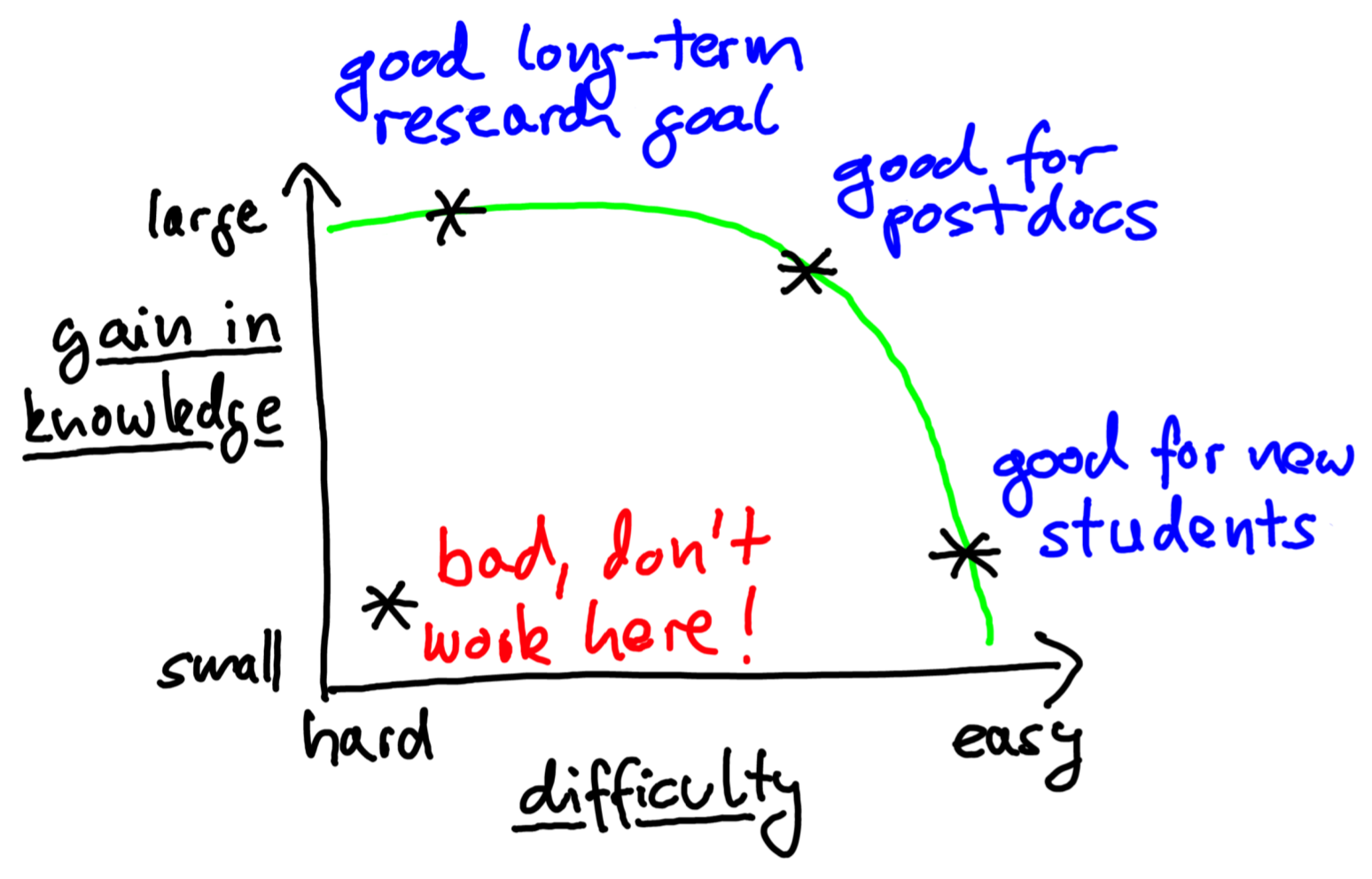

Because I don’t know how to answer Sergey’s question, at first I thought that I wouldn’t have much to say on this topic. However, not knowing something hasn’t kept me from writing a 1500-word blog post about it. After some pondering, I thought it might be useful to review what other people have said on this topic. If you spend some time with Google, you’ll find expert advice on how to choose a good research problem. For example, in Uri Alon’s paper “How To Choose a Good Scientific Problem”,1 there is a nice graphic (here reproduced as Figure 1) ranking potential problems according to their difficulty (hard to easy) and according to the gain in knowledge their solution would provide (small to large). Easy problems with a small gain in knowledge are good beginner problems, hard problems with a large gain in knowledge are good long-term goals for an established researcher, and easy problems with a large gain in knowledge are perfect for a postdoc. And nobody should work on hard problems that lead to small gains in knowledge.

Figure 1: Pareto front of worthwhile research questions. Research questions can be ranked according to difficulty (hard to easy) and gain in knowledge (small to large). The best problems are those that provide the maximum gain of knowledge for the chosen difficulty level. One should never work on hard problems that provide little gain in knowledge. After U. Alon (2009).

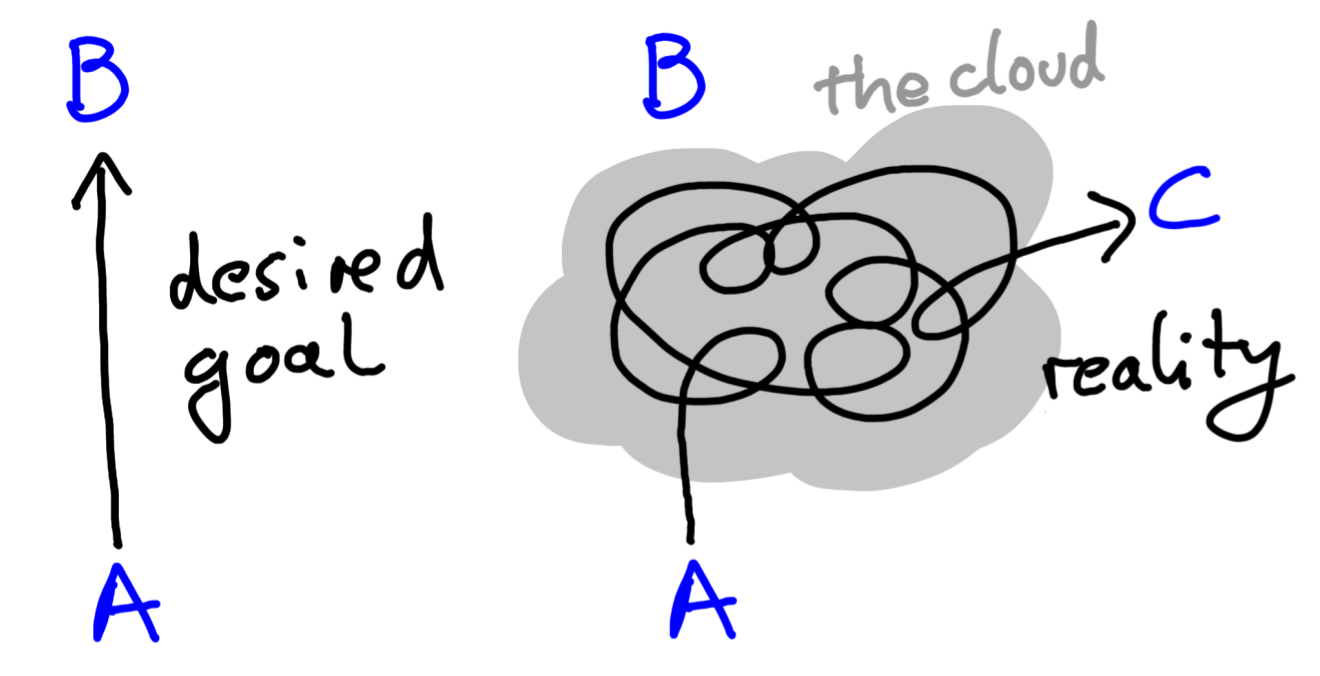

This is all nice and well, until you realize that it is basically impossible to rank problems a priori along either dimension. Uri Alon’s paper explains why. Science does not normally progress in a direct path from A to B. We may intend to work towards B, but on our way there we get stuck in “the cloud,” where every attempt to get closer to B fails, until eventually we give up and go for C, a problem that we hadn’t even considered beforehand (Figure 2). The two immediate consequences of this process are that (i) we don’t know how hard it will be to get from A to C, and (ii) we don’t know how much of a gain in knowledge C will provide, in both cases because we don’t even know C exists when we start. Thus, even though Uri Alon’s ranking of problems along difficulty and gain in knowledge is beautiful and convincing, it is also quite useless.

Figure 2: How we would like to do science (left) and how it actually works (right). Here, A represents what we currently know and B represents what we would like to know. Our desire is to move from A to B in as direct a line as possible. However, we usually get stuck as we are approaching B, things don’t work out, and we keep taking detours and going in circles. Uri Alon calls this state the cloud. Eventually, we give up on reaching B and instead head for C, a new insight that we found while wandering in the cloud. Usually, C represents the solution to a problem we weren’t even aware of when we started. After U. Alon (2009).

So, what can be done? If we keep reading Uri Alon’s article, we find that he makes some useful suggestions on how to pick important problems. He writes:

One of the fundamental aspects of science is that the interest of a problem is subjective and personal. (…) Ranking problems with consideration to the inner voice makes you more likely to choose problems that will satisfy you in the long term. (…) One way to help listening to the inner voice is to ask: ‘‘If I was the only person on earth, which of these problems would I work on?’’ (…) Another good sign of the inner voice are ideas and questions that come back again and again to your mind for months or years. (…) It is remarkable that listening to our own idiosyncratic voice leads to better science. It makes research self-motivated and the routine of research more rewarding. In science, the more you interest yourself, the larger the probability that you will interest your audience.

So, if you’re not sure which problems to work on, work on the ones that excite you!2

Uri Alon is not the only one who has commented on this topic. The famous computer-science pioneer Richard Hamming (of the Hamming distance and Hamming codes) used to give a talk entitled “You and Your Research,” which touches on this issue among other things. You can read a transcript here.3 The whole thing is worth reading. Here, I’ll just cite a few relevant paragraphs. First this one:

When you are famous it is hard to work on small problems. This is what did Shannon in. After information theory, what do you do for an encore? The great scientists often make this error. They fail to continue to plant the little acorns from which the mighty oak trees grow. They try to get the big thing right off. And that isn’t the way things go. So that is another reason why you find that when you get early recognition it seems to sterilize you. In fact I will give you my favorite quotation of many years. The Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, in my opinion, has ruined more good scientists than any institution has created, judged by what they did before they came and judged by what they did after. Not that they weren’t good afterwards, but they were superb before they got there and were only good afterwards.

In other words, don’t try too hard to make a big splash. Just keep working on a variety of problems and see which ones turn out to be useful. While you do so, take notice of things that repeatedly don’t work. Those may be hints that can lead to major insights:

I think that if you look carefully you will see that often the great scientists, by turning the problem around a bit, changed a defect to an asset. For example, many scientists when they found they couldn’t do a problem finally began to study why not. They then turned it around the other way and said, “But of course, this is what it is” and got an important result.

And finally, keep an eye out for great opportunities:

The great scientists, when an opportunity opens up, get after it and they pursue it. They drop all other things. They get rid of other things and they get after an idea because they had already thought the thing through. Their minds are prepared; they see the opportunity and they go after it. Now of course lots of times it doesn’t work out, but you don’t have to hit many of them to do some great science. It’s kind of easy. One of the chief tricks is to live a long time!

What can you do to increase the chance that opportunities come your way? Here is Feynman’s suggestion, as recounted by Gian-Carlo Rota:4

You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state. Every time you hear or read a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps. Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say, “How did he do it? He must be a genius!”

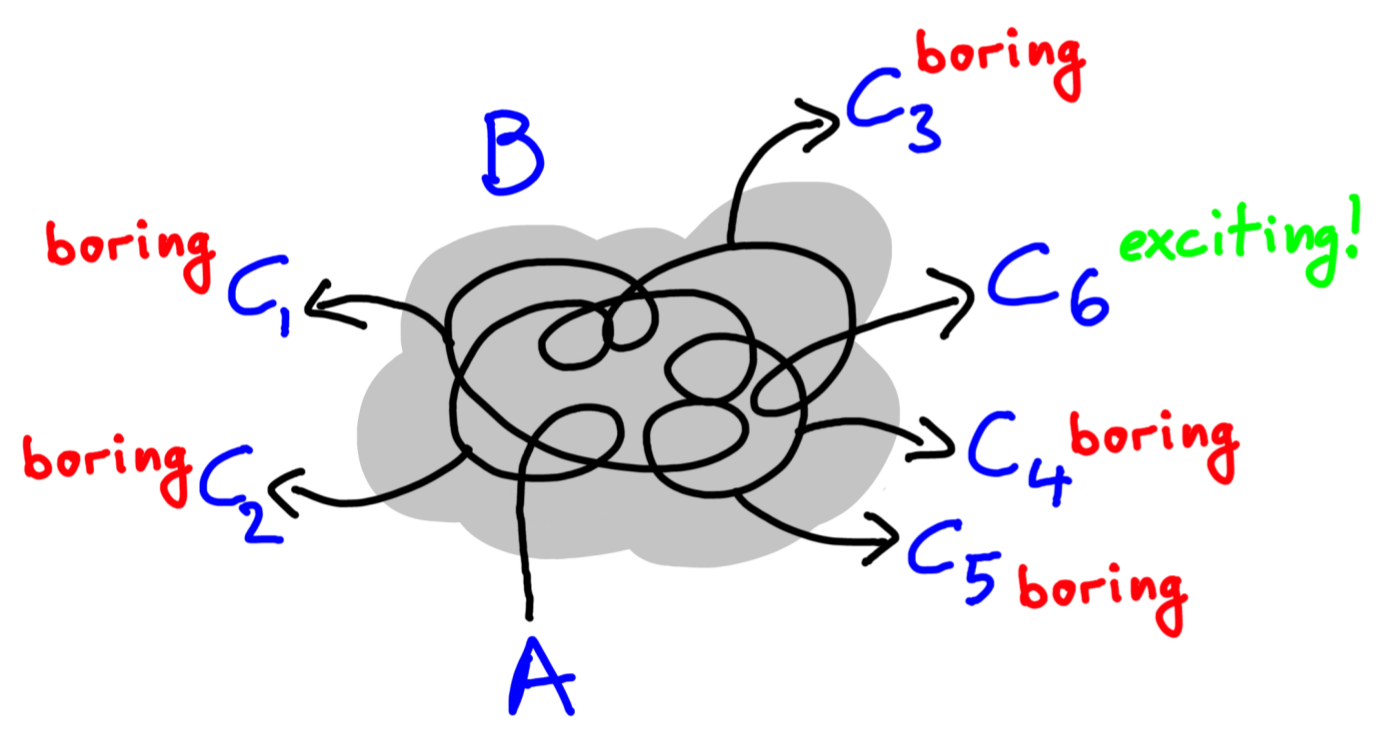

The goal is thus to wander around in the cloud and always keep an eye out for exciting opportunities that may open up. While you’re in the cloud, aiming for B, there may be many C’s that come your way that you could pursue, but most of them will not be worthwhile (Figure 3). However, on occasion, you stumble upon something that is really neat (C6 in the Figure), and when that happens you should drop everything else and pursue that opportunity. I would recommend applying the following test: Do you personally think you’ve stumbled upon an exciting opportunity? If yes, go for it. If no, keep looking for something else to work on.

Figure 3: Scientific opportunities in the cloud. While we are stuck in the cloud, we encounter all sorts of new insights. Most of them are boring, however, and we shouldn’t pursue them further. But, on occasion, we stumble upon an exciting new insight. When this happens, great scientists drop everything else and seize the opportunity.

In this whole process, you might wonder what’s the point of B. If we never get to B, do we need it in the first place? I think we do. B gives us a broad sense of direction while we’re not sure where we’re going in the cloud. Until we have identified an exciting opportunity C, we might as well keep chasing B. Who knows, with luck, we might even manage to get to B at some point. It happens on occasion.

U. Alon (2009) How To Choose a Good Scientific Problem. Mol. Cell 35:726-728.↩︎

It should be noted here that the degree to which a problem is of interest to the broader scientific community depends also on how well it is marketed. You can pick problems you know the community finds interesting, or alternatively you can convince the community that they should find interesting what you are working on. Many of the very successful scientists do the latter. In fact, fame and recognition often go to the person who convinced the community that a problem was worthwhile, not to the person who actually solved the problem in the first place.↩︎

Hamming gave this talk many times. The transcript available here is from March 7, 1986. There is also a video recording, from June 6, 1995. The transcript and the video are largely identical, but I found that the video added a few interesting points that weren’t in the transcript.↩︎

G.-C. Rota (1997) Ten Lessons I Wish I Had Been Taught. Notices of the AMS 44:22-25.↩︎