I came across an interesting paper1 that derives a mathematical relationship between the total number of citations a scientist has received, \(N_\text{tot}\), and the scientist’s \(h\) index.2 The paper, written by Alexander Yong, argues that for typical scientists, \(h\) is given simply as 0.54 times the square-root of \(N_\text{tot}\). The paper also derives confidence bounds on this estimate, and it shows that scientists who have written only a few highly-cited works will generally fall below this estimate. While the paper is set up as a critique of the \(h\) index, I think it shows that the \(h\) index works largely as intended. It measures the total amount of citations a researcher has received, but it adequately down-weighs the effect of a few extremely highly cited works in a researcher’s publication list.

The argument of the paper goes as follows: Let’s consider all the possible ways in which a researcher’s \(N_\text{tot}\) citations may be distributed over a number of publications. On one extreme, the researcher could have written a single article, which has been cited \(N_\text{tot}\) times. On the other extreme, the researcher could have written \(N_\text{tot}\) articles, which all have been cited exactly once. And of course, there are many possibilities between those extremes, where some articles receive more citations and others fewer. The paper then assumes that all these different ways in which \(N_\text{tot}\) citations can be distributed over one or more articles are equally likely, and calculates the expected \(h\) under that assumption. That value, it turns out, is approximately \(0.54 \times N_\text{tot}^{1/2}.\) The paper then tests this relationship for a number of famous mathematicians (Fields-medal winners and members of the National Academy of Sciences) and finds that it generally works quite well, though typically as an upper bound. It is rare for a scientist to have \(h\) exceed the predicted value of \(0.54 \times N_\text{tot}^{1/2}.\) On the flip side, many scientists who have written famous, highly cited books have an \(h\) quite a bit lower than the predicted value, because the books cause the total citation count to be overinflated.

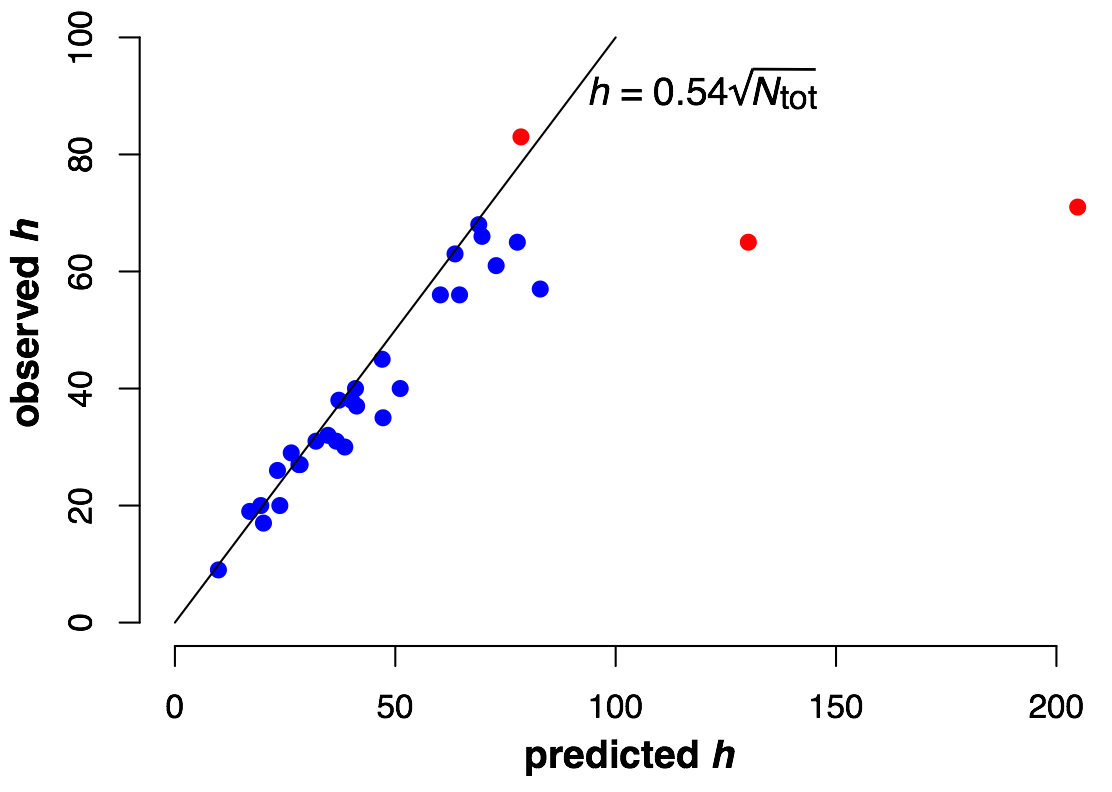

I wanted to know to what extent this formula worked in a different field. So I tested it on the members of my department. For each faculty member3 of the Department of Integrative Biology, I obtained their total number of citations and their \(h\) index from Google Scholar, and then I plotted the observed \(h\) against the predicted \(h\) using Yong’s formula (Figure 1). As you can see, the formula works remarkably well. Almost everybody falls right on top of the line. Importantly, this sample covers a wide range of different career stages.

Figure 1: Observed vs. predicted \(h\) for 29 faculty members in Integrative Biology. Members of the National Academy are plotted in red.

Three faculty members are plotted in red in the figure: those are members of the National Academy, and they are the highest-cited scientists in the department. Interestingly, two have very high total citation counts but, in comparison, not that high of an \(h\) index, while one has the highest overall \(h\) index with comparatively fewer citations. The former two both have written famous books, and many of their citations are to these books. By contrast, the latter scientist stands out by having published a particularly large number of articles that all have been well cited. In fact, that scientist is performing slightly better than the \(h = 0.54 \times N_\text{tot}^{1/2}\) prediction, a truly remarkable result at that high of a total citation count.

In summary, I find that the predicted relationship between \(h\) and \(N_\text{tot}\) works well in my field. However, since major deviations between this relationship can be observed for scientists with a few extremely highly cited works, I prefer using \(h\) instead of \(N_\text{tot}\) to estimate a scientist’s total impact on their field.

A. Yong (2014). Critique of Hirsch’s Citation Index: A Combinatorial Fermi Problem. Notices of the AMS 61:1040-1050.↩︎

The \(h\) index is the number of papers a scientist has written that have received at least \(h\) citations. For example, if you have \(h = 10\), then you have written 10 papers that have been cited 10 or more times. You may have written more than 10 papers total, but none of the other papers you may have written has received more than 10 citations yet.↩︎

To be precise, each faculty member with a Google Scholar profile. This covers almost but not exactly the entire department.↩︎