Today I posted a tweetstorm on publishing an article with F1000Research that was originally commissioned by Springer:

- We just published this article in @F1000Research because of @SpringerNature's abusive licensing practices. https://t.co/Xx88jkA3ec — Claus Wilke (@ClausWilke) October 16, 2017

I received several requests to turn this into a blog post, so here we go. The blog post consists mostly of the text of the tweets, with some minor edits and clarifications.

We just published this article in F1000Research because of Springer’s abusive licensing practices. The article was originally written to become a chapter in a Springer book on methods in protein evolution, and it describes key protocols my lab uses to measure site-specific rates in proteins and correlate them with protein structure. We’ve published extensively on this topic in recent years, see e.g. Jack et al., PLOS Biology 2016.

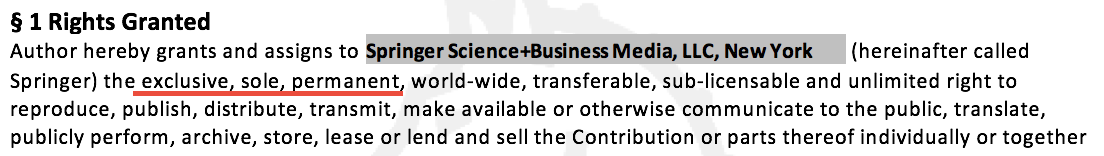

However, as a precondition of publishing, Springer wanted us to assign to them the exclusive, permanent copyright to the work (Figure 1). In essence, they wanted us to donate our work to them so they could lock it behind a paywall and make money off of it. I were an unpaid intern at Springer while writing the article, Springer’s request would violate US labor law. But since I’m an independent agent, I guess I’m allowed to make donations to a commercial entity.

Figure 1: The copyright agreement I was asked to sign. Key phrases of the agreement are underlined in red. Most important is the word exclusive, which implies that the authors (us) lose any rights not explicitly enumerated in the remainder of the agreement.

You might ask me: “What exactly is it you are complaining about here? People sign these agreements all the time, as have you in the past. How is this case any different?” The difference is that in this case, there’s virtually no benefit, even non-monetary, that Springer provides to in return. I understand that people might be willing to sign away their copyright in return for Nature paper that gets them their next job or grant.1 But a chapter in a methods book? That isn’t even peer reviewed? It doesn’t bring me (or my trainees) any prestige, unless the article is widely available and people use it and cite it a lot. But Springer explicitly doesn’t want that, because they make money from people buying the book to read the method.

I cannot let Springer own key protocols from my lab.

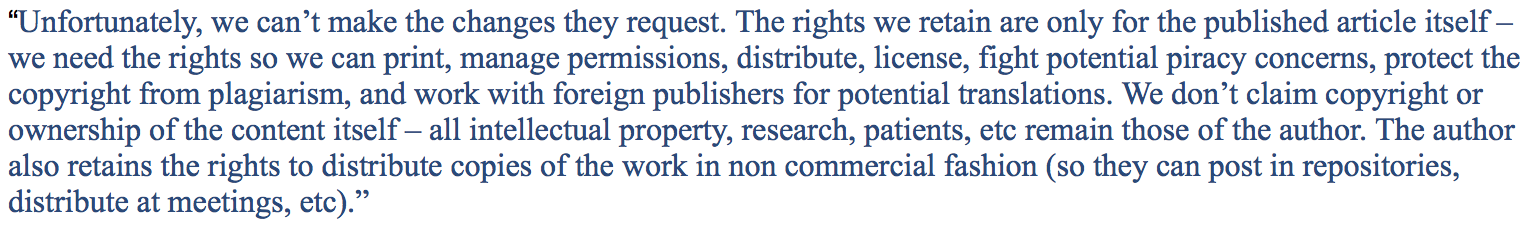

As if this alone weren’t enough, I also found my conversations with them disingenuous. In particular, when I asked for a non-exclusive agreement, they lied to me about what the agreement says (Figure 2). Note the phrasing “We don’t claim copyright or ownership of the content itself” in this is response by Springer. It is blatantly false. Remember the copyright agreement is exclusive. This means the authors lose all rights except those explicitly stated as retained.

Figure 2: Statement by Springer representative. A Springer representative made this statement when I requested a non-exclusive copyright agreement.

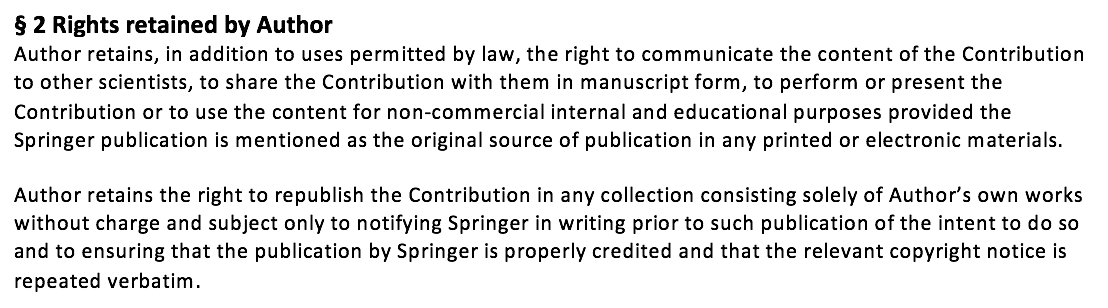

Figure 3: Rights retained under the proposed copyright agreement.

Let’s take a look at the rights that we would have retained (Figure 3). Pay attention to the repeated occurrence of the word “content”. The person who drafted the copyright agreement knew very well that it would cover the contents of the contribution. That’s the point of copyright. So, according to Figure 1, we would have lost the right to communicate the content to non-scientists. This includes, for example, commercial entities that may want to use our protocols. We would also have lost the right to post a preprint of the work. And it is unclear whether we would have been allowed to post it on personal webpages. That depends on whether the visitors of our personal webpages can be considered to be scientists or not. We would certainly have lost the right to publish an updated version of the protocols at some future date with a different publisher. I wouldn’t even have been allowed to this paper in a future anthology of my most influential papers, assuming it would be distributed at some cost. (Unlikely that I’d want to, but that’s not the point.)

For all the above reasons, the paper is now with F1000Research, and you can read it free of charge, copy it, and build on it. Enjoy.

Andrew Rambaut pointed out that Nature (the journal) does not require a permanent, exclusive copyright license anymore. This statement was later disputed by Daniel Himmelstein.↩︎